Ah, the old “energy transfer” question. You knew I had to address it sooner or later, didn’t you? Turns out it was later. But, I just ran across an interesting article that I think may prove quite illuminating on the subject.

What subject? Psychological Stops. As in, why does someone who’s shot superficially, or non-mortally, choose to drop their gun and stop attacking?

It’s an important subject because, while we typically deal with the concept of “incapacitating wounds”, the fact remains that a large percentage of gunfights seem to be ended due strictly to psychological factors, rather than physiological factors (i.e., the person voluntarily decides to stop attacking, instead of being forced to stop attacking.)

How many cases are of psychological stops rather than physical incapacitation? I don’t know of any definitive study that has attempted to classify it. I do know that there are doctors who say that (with treatment) six out of seven people shot by handguns will survive. In a case of true incapacitation (where the person’s body has been so damaged by the bullet that their body itself shuts down and therefore removes their capacity to continue acting voluntarily) the odds would seem to be drastically lower, since true incapacitation usually relies on either the death of, or paralysis of, or the rendering unconscious of the attacker. And rendering them unconscious usually happens through blood loss so substantial that their blood pressure drops below that necessary to keep them conscious and acting. And if they’re losing blood that fast (through a damaged artery or circulatory system organ) then it doesn’t seem likely that emergency responders would be able to get there in time to prevent a total bleed-out.

As such, it seems that a very high percentage of people who are dissuaded from their actions via gunfire, do so not because their body has been so damaged that they cannot continue, but rather they choose voluntarily to stop. (I offer as food for thought my prior articles on just how much damage a human body can sustain and still keep attacking; Peter Soulis put twenty-two rounds of .40 S&W in Tim Palmer and Palmer didn’t stop until the twenty-second round hit him. It can at times be quite difficult to force a determined attacker to stop just through the use of gunfire.)

Incapacitation vs. Psychological Stops

Before continuing, I want to point out one of my prior articles, “An Alternative Look at ‘Alternate Look at Handgun Stopping Power‘.” In that article, I attempted to evaluate the data collected by Greg Ellifritz and put some context into it, as far as how the data could not necessarily be used to draw the type of conclusions that people are wont to draw about data like this (such as “the .40 S&W is the best manstopper, and the .32 ACP has a higher one-shot stop percentage than the 9mm”, or any other such conclusions.) The crux of my argument there was that there was no real delineation in the data between what was a Psychological Stop (i.e., the person shot just gave up) vs. true Incapacitation (which, by my definition, means that the bullet damages the body to the point that the person is no longer capable of voluntary action). And if we don’t know that distinction, we can’t attribute the performance to the bullet alone.

I believe that in my prior article I laid out some good reasoning for how we couldn’t tell which were Psychological Stops, and which were true Incapacitation. Accordingly, I think the percentages listed simply cannot be relied upon as a predictor of how effective any particular caliber will be in causing an attacker to stop.

However, I’d like to revisit this subject because of a follow-up article by Mr. Ellifritz (who, generally, I do agree with on almost everything else in his articles). Ellifritz published an article on the use of his data to evaluate the .22LR as to its effectiveness for self defense, especially in context with answering some questions raised by readers of his prior articles.

I think Ellifritz’s data sheds some excellent light on a subject that’s been the source of many questions for many people, and that is:

Does Kinetic Energy Transfer Cause Psychological Stops?

So here’s the crux of the matter, in a nutshell: there are two different schools of thought on handgun bullet performance, the Light & Fast vs. the Slow & Heavy. The Light & Fast group typically use terms such as “energy transfer” or “hydrostatic shock” to talk about how a bullet affects a person’s physiology; the Slow & Heavy group generally ignores all that and focuses on what actual tissue was destroyed by the bullet itself. The Slow & Heavy school (of which I am a member) say that if you poke a hole in someone’s vital organs, they’re going down. And if you don’t poke a hole in their vital organs, they won’t have any physical reason for stopping. They MAY choose to stop, but there isn’t necessarily any anatomical reason for them to have to stop.

The Light & Fast group, on the other hand, focuses on the size of the temporary cavity created, and some argue that the faster the bullet “transfers its energy to the target”, the more likely the person is to stop their attack. The idea behind this philosophy generally involves the notion that a “rapid energy transfer” will cause incapacitation.

I don’t know about that; I know of zero studies that have been done that show that there is any increased likelihood of a psychological stop due to energy transfer, and don’t know how an ethical researcher could even begin to undertake to test for such an effect. Seriously, such testing could only be conducted against human subjects (since only humans have human psychology), and would likely require a very large sample size before you could filter out the noise and start to see real patterns emerging. Probably at least a thousand data points would be needed, and I think it’s safe to say we aren’t going to see any researchers shooting a thousand people to see what percentage are likely to just “give up” in a gunfight…

So the question arises — is a “Light & Fast” bullet more likely to cause a psychological stop, than a “Slow & Heavy” bullet is? Does more energy transferred make a person more likely to quit a gunfight? Would a fast-energy-transfer gunshot be more painful than a Slow & Heavy gunshot?

Again, these are all questions we cannot answer scientifically, without some serious ethical breaches of protocol! But, using Ellifritz’s .22LR article, I think we can take a good step towards clearing up some of the confusion and sorting through the fog.

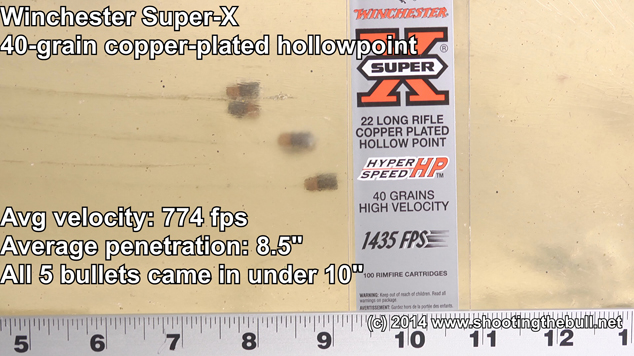

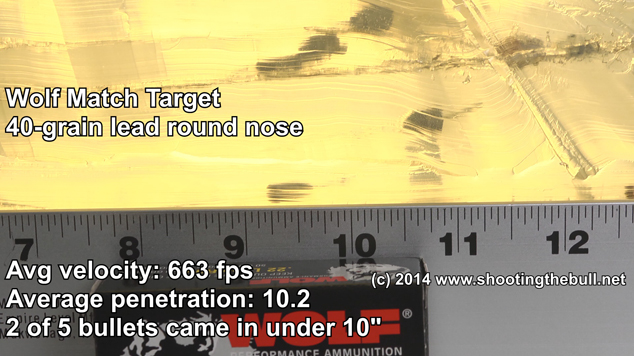

Here’s the thing that stood out to me, in Ellifritz’s studies — while we don’t know what percentage of his data subjects were true psychological stops vs. true incapacitation, we do still have a lot of data to examine on people who were shot. And, in Ellifritz’s article on .22LR, he makes some insightful observations, specifically that the .22LR is the least likely of all calibers to cause a true physically incapacitating shot. Due to the small diameter, light weight and low velocity of the .22LR, its penetration capabilities are less than the other calibers are, so the likelihood of it having caused substantial body damage sufficient to cause true incapacitation is reasonably presumably lower than other calibers.

And yet — a whole lot of people in his study stopped attacking after getting shot with a .22LR. According to his data, 60% of the people who were hit with a .22LR round, stopped their actions. Only 31% didn’t, regardless of how many rounds they were hit by.

What does that tell us?

Well, it tells me that people don’t like to get shot, and getting shot is frequently enough to get a person to give up. Even if the bullet doesn’t mortally wound you, the sheer shock and horror and fear of being hit by a bullet (any bullet) and the attendant pain, blood, and fear of imminent death that all can be expected to occur in gunshot recipients, is very likely enough to get that person to say “screw this, I’ve just been shot, I’m not sticking around to get shot again.”

Going by Ellifritz’s data, the percentage of people who stopped after getting shot by a single shot of a .22LR, is about the same as the percentage of people who stopped after getting shot by a single round of .380, or .357 Magnum, and it’s even higher than the percentage of people who stopped after getting shot with a single round of .38 Special, 9mm, .40 S&W or .45 ACP. Seriously, that’s what the data shows.

How many of those stops were psychological? We cannot know, the data was not gathered in a way that would tell us that, but seeing as the percentages are relatively quite consistent (from 47% for the 9mm up to 62% for the .22), and knowing that the .22LR is the least powerful of all the cartridges tested and therefore (as Ellifritz eloquently reasoned) the least likely to be doing true physical incapacitation to the attacker’s body, I think it’s fairly safe to say that a whole lot of these 47% to 62% of “one shot stops” were strictly psychological. Again, this is supported when we look at other shooting scenarios (see my prior articles referenced in this article) where five hits of 9mm or .38 Special, or 7 hits of .45, or even 22 hits of .40 S&W, were not enough to bring an attacker or an officer to the point of incapacitation, it seems unlikely that a single .22LR bullet is likely to drop an attacker through sheer force of incapacitation (without a direct hit on the central nervous system or circulatory organ, that is).

So now we return to the central question of this article — how much of a role is Energy Transfer likely to play in psychological stopping? Again, and sorry to repeat it so many times but it’s important to be clear on this: we don’t know, and we cannot truly know definitively. We can only look at the information in front of us and try to draw what conclusions we can. And the conclusion I draw is: “Energy Transfer” doesn’t necessarily mean squat as far as causing an increased likelihood of a psychological stop.

The reason I say this is specifically because of Ellifritz’s .22 data. If you think about it, if higher levels of energy transference were going to cause people to be more likely to quit attacking, then shouldn’t the percentage of one-shot stops be much higher for the high-energy rounds (like .40 S&W or .357) than they would be for the tiny-energy .22 round? Or, let’s put it another way — the .22 doesn’t really have much energy to transfer at all. From a handgun, the .22lr is usually going to deliver less than about 90 ft/lbs of energy, as opposed to the 300 to 500 ft/lbs one is likely to see from a 9mm, .357 Magnum, .40 S&W, or .45 ACP. So — if the amount of energy transferred was a strong indicator of the likelihood of a person to psychologically stop, then shouldn’t the 1-shot stop percentages be much higher for the higher-energy rounds? And yet, they’re not. The highest-energy round on Ellifritz’s list, the .357 Magnum, has a one-shot stop ratio that’s practically identical to the lowest-energy round on his list (the .22LR). It’s 61% vs. 60%! How can those be the same, when a .357 delivers 430 ft/lbs or more, and the .22LR delivers less than 90? The leading theory to me is: because “energy transferred” doesn’t matter as much as people may like to think.

Surely the .357 creates a much bigger temporary cavity. Surely the .357 delivers more pain and transfers more energy — heck, it’s got about 5x as much energy to transfer. And yet… according to the numbers, the (fundamentally) same percentage of people hit with the low-energy round stopped attacking after one hit, as those who were hit by the high-energy round.

One could argue that a higher percentage of the .357 bullet recipients were incapacitated overall than the .22LR bullet recipients. While we cannot know for sure, the data does show that while the one-shot-stop percentages were fundamentally the same, the % of those who “would not stop no matter how many times they were shot” is much higher for .22LR than it was for .357 magnum. In the shootings Mr. Ellifritz evaluated, 31% of those shot with a .22 did not stop, whereas only 9% of those shot with the .357 didn’t stop. Does that prove that the higher energy round was the more effective stopper? Yes indeed — as you’d expect. But — I don’t think it proves it to be any more effective for psychological stops. I think the .357 should obviously be expected to be a more potent physical incapacitator than the .22, and I think the “% that did not stop” field shows that perfectly well. However, I think that same field also demonstrates the point I’m trying to make — those that DID stop from the .22, are more likely to have CHOSEN to stop.

Because the .22 is less likely to have caused the type of damage that forces someone to stop than the .357 is, it leaves the question open: then WHY did those who were shot just once by the .22, stop at all?

And the answer can only be — they were mainly psychological stops.

What about the .357 then — it had the same % of one-shot stops (61% vs. 60%) — can we say that it had the same percentage of psychological stops? Again, I don’t think we can draw that conclusion from the data, because it’s clouded by the “% that did not stop” field. I think a decent hypothesis would perhaps be — in any given group of people, regardless of what bullet they’re shot with, a certain percentage is predisposed to giving up right away. Since all the categories showed generally similar one-shot-stop percentages (generally 47% to 61%), I think that is a hypothesis that, while unproven, could still reasonably be inferred. However — what percentage of those who would have given up, were in fact instead incapacitated? That may be the difference — if someone was forcefully incapacitated (as would be more likely from the more-damaging .357 bullet) then we can’t know whether they would have been a psychological stop or not, because the choice was taken away from them due to true incapacitation. And that may be the answer we see, between the “% stopped after 1 shot” and “% that did not stop” fields.

So that brings us back to — does the higher energy transfer of a high-energy round like the .357 make it more likely to cause a psychological stop than a low-energy round? While we don’t necessarily know, I think that if we stand the question on its head we can draw an inescapable conclusion — those who chose to stop psychologically, from the .22, weren’t doing so because of high energy transfer! The .22 doesn’t have much energy to transfer, and its temporary cavity is positively tiny compared to the high-energy rounds like the .40 or .357. And yet, 60% of those shot by the .22 either chose to stop, or were incapacitated (and, again, the likelihood of those who chose to stop would reasonably be higher for .22 than for the other calibers, because the likelihood of true physical incapacitation would be lower from the .22 as compared to the other calibers). So if (hypothetically) high energy transfer is what causes someone to psychologically stop, then why would anyone who was shot with a .22 psychologically stop? There’s no high energy to transfer!

Therefore, it seems safe to conclude that the level of energy transferred is likely not as significant a factor in causing a psychological stop as it may at first seem.

My guess? Folks who have been shot get scared, and getting shot hurts, and seeing your blood leaking out of you hurts. Plus we’ve been programmed by decades of Hollywood movies to “know” that just the very fact of getting shot means that you are supposed to drop on the ground and die right away. Those factors all weigh on the psychology of someone who’s been shot, and I believe they are the contributing factors that cause a psychological stop, far more than the caliber of bullet or the amount of energy transferred by that bullet. Accordingly, I don’t think that adding more energy or higher velocity is a good predictor for increasing the likelihood of a psychological stop. Now, let’s back up and say — I think more energy, more power, bigger heavier bullets, and more shots on target are all good things — if you could do any one thing that would increase your likelihood of stopping an attack, I’d say more shots on target would be the most important thing. But I’d always advise to carry the most powerful weapon that you can comfortably and accurately shoot. Just because data has been correlated that show a .22LR has been able to cause 60% of the people shot by it to stop attacking, doesn’t mean it’s a good choice for self defense. The more powerful the weapon, the bigger and deeper-penetrating the bullet, the more likelihood you have of causing a true incapacitating wound — and if you do that, then it takes all the guesswork, all the hypotheses, and all the questions and flings ’em right out the window.

First and foremost, place shots properly on the target to cause hits on the vital organs. Second, place as many of those shots on target as you can until the attack stops. Third, place them with the most powerful firearm that you can comfortably and accurately control. Do that, and your likelihood of success in a defensive encounter will skyrocket, far more than worrying about whether your bullet transfers enough kinetic energy or what some one-shot-stop study says.