“Stopping Power.”

Are there any two words, when put together, that are more likely to start a heated internet debate in gun forums than those two? (actually, probably “caliber wars”, but other than that, I can’t think of many).

I just did a big article on “stopping power” but I want to go a step further and expand on this a bit, because I think this is one of the most confusing, frustrating, misleading, and dangerous subjects in all of gundom. (made up a word there — take that, spellchecker!)

So the topic of today’s discussion is an article published by Greg Ellifritz on the Buckeye Firearms Association website, entitled “An Alternate Look at Handgun Stopping Power”. In this article, which has spread throughout the internet forums, Mr. Ellifritz compiled a decade’s worth of data on shootings, and compiled the data into some tables, that enable readers to make some comparisons. Some very, very faulty comparisons.

Before I get into this, let me say that I really appreciate all the effort Mr. Ellifritz put into this. It seems like he was seriously trying to make some sense out of what is a very confusing subject. It must have been a lot of work, and I believe his heart was in the right place, just as I believe that Marshall & Sanow set out with the best of intentions to find the answers that people really wanted to know.

The problem is, they asked the wrong questions. Or didn’t ask the right questions. And in the end, that results in statistics that are highly misleading and can lead people to draw completely unwarranted conclusions from the data presented! And that’s bad. Regardless of how good the intentions were, the resulting posted information may lead (or empower) people to draw unwarranted, inaccurate, or just plain faulty conclusions.

The .380 ACP Is “The King Of The Street”???

Let me show you what I mean. Let’s take the example of Ellifritz’s compiled data on the .380 ACP. According to this article, you could easily draw the conclusion that the .380 is the overall most effective handgun round of all the common self defense weapons(!) Bet that took you by surprise, didn’t it? But if we take the data at face value, there’s no question — the .380 is better at stopping people than the .40 S&W, it’s better than the 9mm, it’s better than the .45 ACP. Or, at least, that’s the conclusion one would be forced to reach, if they take the data at face value! Look at these categories:

| .22LR | .380 ACP | .38 Special | 9mm | .357 Mag/Sig | .40 S&W | .45 ACP | |

| % of hits that were fatal | 34% | 29% | 29% | 24% | 34% | 25% | 29% |

| Average # of rounds to incapacitation | 1.38 | 1.76 | 1.87 | 2.45 | 1.7 | 2.36 | 2.08 |

| One-shot-stop % | 31% | 44% | 39% | 34% | 44% | 45% | 39% |

| % actually incapacitated by one shot | 60% | 62% | 55% | 47% | 61% | 52% | 51% |

Those are (many of) the numbers reported in the article. What immediately jumps out at you? I’ll tell you what I see:

According to this data, the .22LR is the deadliest bullet on the market. 34% of the .22LR shots were fatal, versus (for example) only 24% of the 9mm rounds. So should people ditch their 9mm guns and trade them in for .22LR’s? Not so fast, let’s keep looking… what if you ignore killing power and just go for stopping power — what caliber stops people in just one shot? Well, according to this data, that’d be the .380 ACP, which has a 62% rating of people being incapacitated by just one shot(!) That’s a much higher percentage than, say, 9mm, which had only a 47% record. So surely, .380 ACP is a better choice for self defense than 9mm (or, for that matter, 40 S&W, or .45 ACP, or .357 Magnum). That’s what the data is telling us, right?

How about if you want the fight to stop quickly — as in, using the fewest number of hits before the attack stops? Well, according to the data, you’d want to be using a .22LR for that — after all, people who are hit by less than 1.4 shots of .22LR stop attacking, whereas with .357 Magnum it takes 1.7 bullets, right? Surely the .22LR is a more powerful manstopper than the .357 Magnum, according to the data, right?

Clearly all these conclusions are complete poppycock. Anyone drawing these type of conclusions would be sorely and severely mistaken. So what’s going on here? Is the data faulty? Or is there some “magical” property of the .22LR that makes it more effective in stopping people than a .357 Magnum is? Of course not. And Mr. Ellifrtiz doesn’t believe that either — he even states in his article that “I really don’t believe that a .32 ACP incapacitates people at a higher rate than the .45 ACP!” Even though that’s what the data shows — his data shows that for a % of people incapacitated by one shot, the .32 ACP did it 72% of the time, whereas the .45 ACP did so only 51% of the time.

So what’s going on here?

The Problem Is That The Wrong Questions Were Asked

The data is woefully incomplete. It doesn’t ask the right type of questions. And because the data is incomplete, NO USEFUL CONCLUSIONS CAN BE DRAWN FROM IT.

What’s missing? Here are a few examples:

1. HOW were the people incapacitated? In fact, what was the definition of incapacitation? As near as I can tell, the author is using the term “incapacitation” interchangeably with the notion of the person stopping their attack. But there’s a massive disconnect here — there’s a huge difference between a person CHOOSING to stop, and one being FORCED to stop. “Incapacitation” means (and should mean) that the attacker no longer has the capacity to attack — i.e., that they’ve been rendered paralyzed, unconscious, or dead. No indication of this is given in the data; instead, anyone who stopped without landing another blow or firing another shot is considered “incapacitated.” That’s grossly misleading, because it ignores the fundamental question of whether the person was CAPABLE of continuing the attack or not.

2. There’s data on the # of rounds that are fatal, but there’s no indication given as to WHEN the attacker expired. And that makes a huge difference! If someone is swinging a crowbar at your head, and you shoot him, does it matter to you if your attacker dies on the operating table 2 hours after they shoved that crowbar through your brain? To me, whether they die or not is irrelevant; the important question is whether or not I stopped the attack before they did serious bodily harm or death to me or someone I was protecting. If you shot someone with a .22LR in the gut, and they didn’t get treatment, they would likely die — in about three days, from infection. But that would have zero determination on the outcome of your immediate fight! Remember, self defense isn’t about killing your attacker, it’s about stopping them — so eventual fatality is irrelevant in the discussion. Incapacitation (using the proper definition) is the crucial data point — and that’s what’s not properly represented here in this data.

3. What type of gun was used? No indication in the data is given, but it makes a tremendous difference! Let’s use .22LR for example — a 32-grain CCI Stinger from a 1″ barrel NAA mini revolver delivers around 40 ft/lbs of energy. The exact same bullet, fired from an 18″ rifle, delivers 3x to 4x as much energy. Three or four times as much! Yet no indication is given (although we can presume that the rifle is irrelevant from the data above, as the author included a separate category for all rifles). So let’s just stick with handguns — how about with the .357 Magnum? Let’s use a 125-grain Hydra Shok. Was that bullet fired out of a little Bond Arms derringer with a 2.5″ barrel? If so, it’d travel at about 1100 feet per second and carry 335 ft/lbs of energy; but what if it was fired from a 4″-barrel police duty revolver? In that case, it’d be traveling at about 1550 feet per second and carry 667 ft/lbs of energy! Twice as much, from the exact same cartridge, all depending on just a simple change of barrel length. It makes a difference. It makes a big difference.

Heck, let’s take it a bit further — a 9mm normally uses a 124-grain bullet, and from a Glock 17 a Hydra Shok travels at about 1100 feet per second. That’s the same diameter, size, weight, and velocity as the .357 Magnum from the 2.5″ barrel! So can we draw the conclusion that a .355-diameter Hydra-Shok weighing 124 grains and moving at 1100 feet per second would perform fundamentally identically to a .357-diameter Hydra-Shok weighing 125 grains and moving at 1100 feet per second? Of course we could; there’s practically no difference whatsoever. So how are we to know what the data in the article represents? Does the .357 Magnum data show the results of 335-ft/lbs, or of 667 ft/lbs? We don’t know. But it makes a difference. Anyone thinking that the .357 Magnum cartridge is magical on its own, without considering the gun barrel it’s coming from, would be making a disastrously misinformed decision.

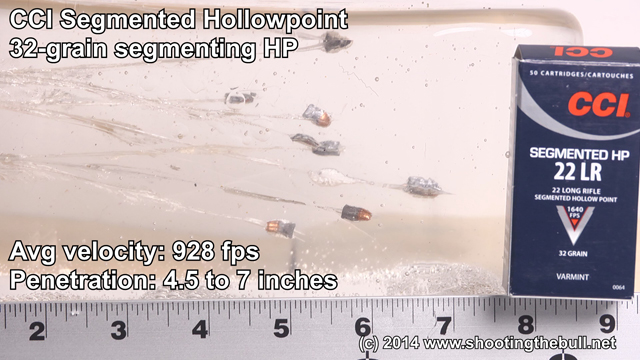

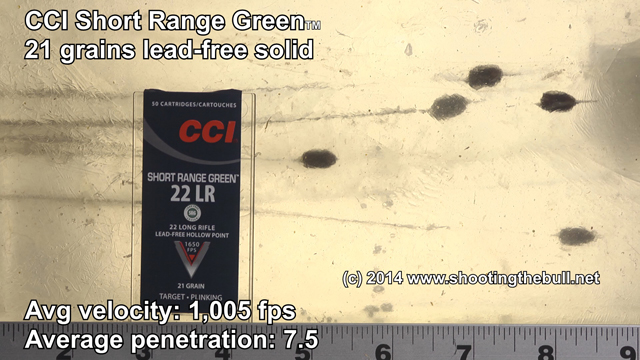

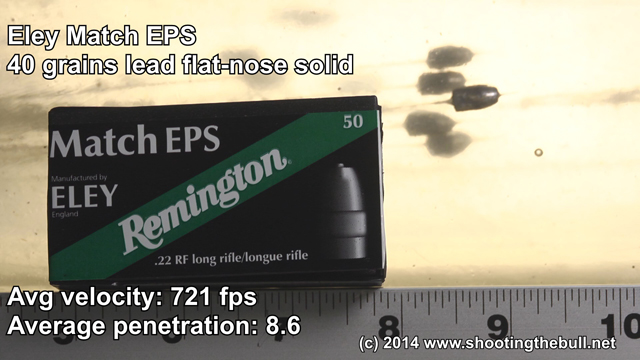

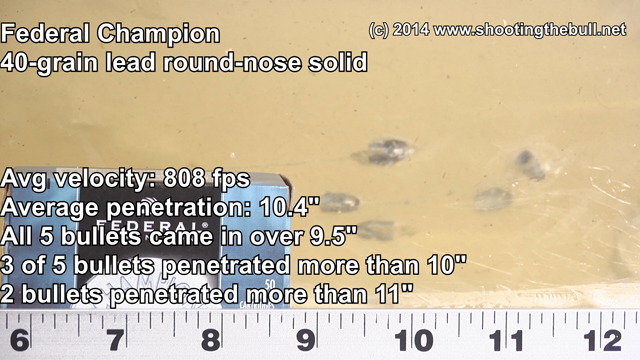

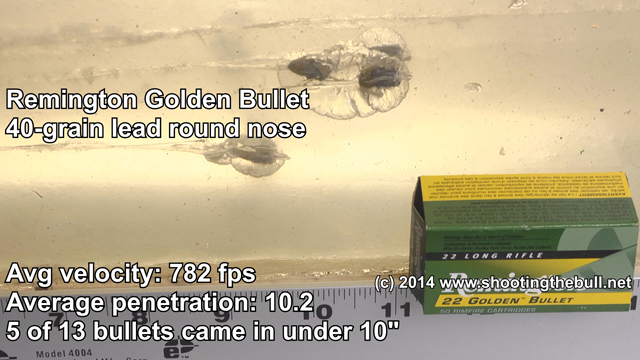

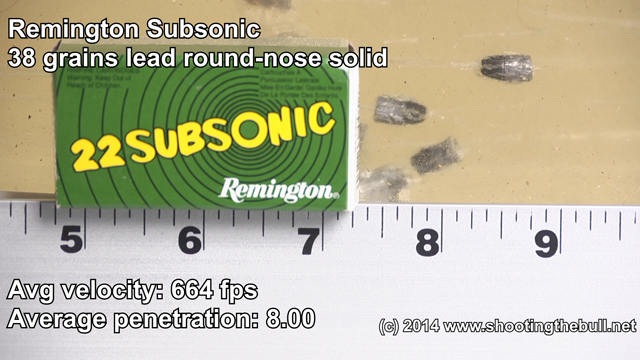

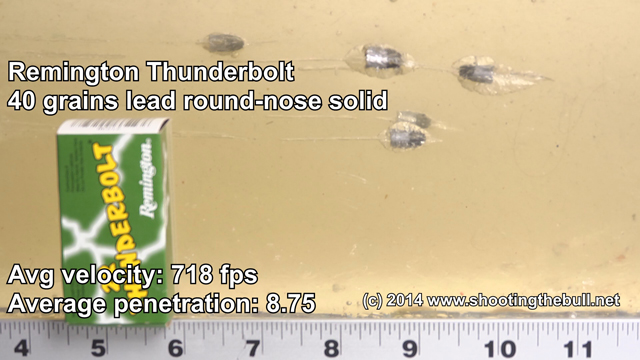

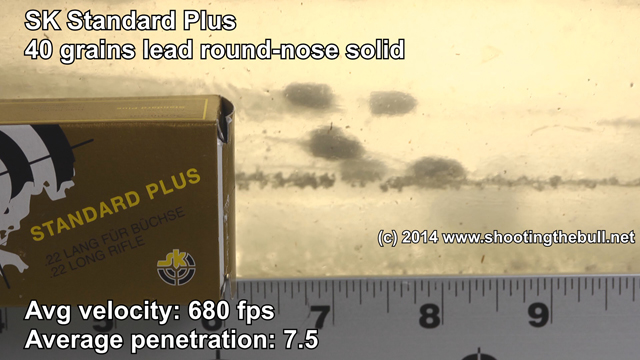

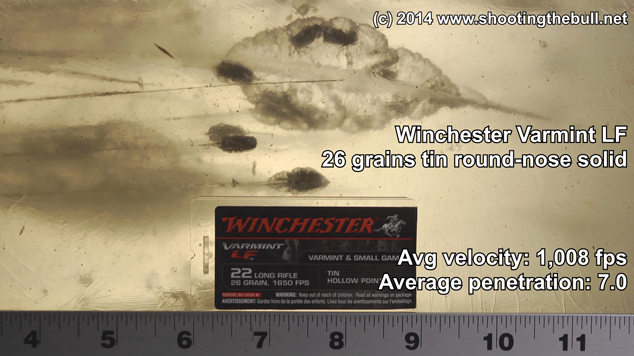

4. What TYPE of bullets were used? We don’t know — the data presented to us makes no distinction whatsoever. We could be looking at hollowpoints, or roundnose full metal jackets, or flatnose FMJs, or wadcutters, or ratshot shotshells, or frangibles. We don’t know what weight of bullet (and bullet weight can vary widely within any given caliber; 9mm ranges from around 50 grains on up to 147 grains). Are we being asked to assume that a 50-grain frangible is exactly as effective in “stopping power” as a 147-grain hollowpoint, which is exactly as effective as a 95-grain roundnose FMJ? Apparently we are, but that is a plainly silly thing to even consider. Furthermore, Mr. Ellifritz’s data includes military shootings, which would usually mean FMJ/ball ammo, which is less effective in damaging tissue than hollowpoints are. The 9mm data listed includes over half the shootings involving ball ammo, and that skews the data on the 9mm’s effectiveness (as Mr. Ellifritz rightly points out in his article). But doesn’t that acknowledgement really point out the flaw in the whole exercise? Acknowledging that certain types of ammo are more effective than others, and then lumping them all together in the same category, prevents us from drawing the proper conclusions here.

5. Did the bullet WORK? If it was a hollowpoint, did it expand? We don’t know, because the data presented gives us no way to draw any sort of conclusion. I for one would be very interested in knowing what percentage of bullets fired failed to work properly, and how that affected incapacitation, but we don’t know. And I’m not complaining about Mr. Ellifritz’s efforts; he did the work he did, and I didn’t, so I don’t get to complain — but I still feel it is my obligation to point out why we can’t draw comprehensive conclusions from the data as presented.

So, in short — we don’t know what type of gun was used, we don’t know what the barrel length was, we don’t know what type of ammo was used, we don’t know what velocity the bullet traveled, and we don’t know why the person stopped attacking (i.e., did they voluntarily just choose to stop, or did the impact of the bullet force them to stop?) How can you draw a reasonable conclusion from any of this?

Here’s the conclusions I think we can draw from it:

1. People do not like getting shot by bullets, and the pain, fear, shock, adrenaline, or panic that comes about by getting shot is frequently enough to stop someone from continuing to attack you. And if someone is inclined to stop attacking you if they get shot, then the actual caliber they get shot with doesn’t seem to matter much. If someone’s going to stop because they feel the pain of a shot and they see themselves bleeding, it probably doesn’t make much difference whether they got shot with a .22 short or a .357 Magnum; in either case there’s a loud bang, pain, and blood. So for this subset of attackers, caliber probably doesn’t matter much. For that matter, bullet type wouldn’t matter much in that case either (hollowpoint or FMJ), barrel length probably wouldn’t matter, heck, not much of anything matters other than having the ability to make a loud noise and poke some manner of hole in the attacker’s body.

I think this situation is fairly common, and represents a large portion of self defense shootings. I don’t have the statistics so I can’t definitively prove it, but I believe this to be a reasonable conclusion based on the notion that about 6 out of 7 people shot with handguns survive. True incapacitation (forced unconsciousness due to blood loss, or death, or paralysis) could reasonably be presumed to have a much lower survival rate. Therefore, it seems reasonable to conclude that most people who stop an attack after getting shot, have CHOSEN to stop that attack, rather than been FORCED to stop their attack.

2. Sometimes people will not choose to stop attacking, even after being shot, and you will have to FORCE them to stop. And in that case, caliber matters very much — as does gun size, bullet speed, bullet construction, bullet performance, shot placement, and all the other factors that go into the overall process of a bullet colliding with flesh. If you are in a situation where you have to FORCE someone to stop, it will be through the bullet damaging their body in such a way that they cannot continue to act voluntarily. And that means damaging their central nervous system (resulting in paralysis), or their brain stem (resulting in immediate death), or in the bullet damaging their circulatory system such that they bleed out rapidly and lose consciousness (a situation which, left untreated, will likely also result in their death). Can your choice of gun and ammo, working together, accomplish that? That’s the big question — and that’s the question that is left completely unanswered by the types of data examinations that we can conduct based on Ellifritz’s or Marshall & Sanow’s work. I mean, let’s get real here — according to the Ellifritz data, a .44 Magnum is less effective in stopping attackers than a .32 ACP! The data shows that 72% of people were incapacitated by one shot from a .32 ACP, whereas only 53% were incapacitated by a single shot of .44 Magnum. Yet a .44 Magnum is vastly more powerful and destroys much more flesh. The .44 Magnum is far more likely to be able to cause a truly incapacitating hit than the .32 ACP ever would be.

So, really, where does that leave us? I think it leaves us here:

A. If someone’s going to choose to stop attacking after being hit by a shot, any gun in any caliber is likely to work as well as any other gun in any other caliber, so this should be completely ignored in your choice of carry weapon and caliber. It’s not that “caliber doesn’t matter”, it’s that it doesn’t matter in this particular case — therefore, you should most definitely NOT choose your gun and ammo based on “well, they’re all the same”; instead, you should ignore all such data because it can seriously mislead you into choosing something that’s underpowered. Do you want to bet your life on the hope that an attacker will just choose to stop? I know I wouldn’t want to bet my life on that, I’d want to put the odds more in my favor.

B. If someone’s not going to choose to voluntarily stop attacking, and you have to force them to stop, you would be best served by the gun/ammo combination that is capable of causing the most damage possible, and that you can shoot most accurately. The specific caliber isn’t nearly as important as the amount of damage done to the target. You have to view the gun and ammo as a complete system that results in damage being done to the target; a powerful bullet being fired from a tiny gun may likely not be as powerful or do as much damage as a less-powerful bullet being fired from a bigger gun.

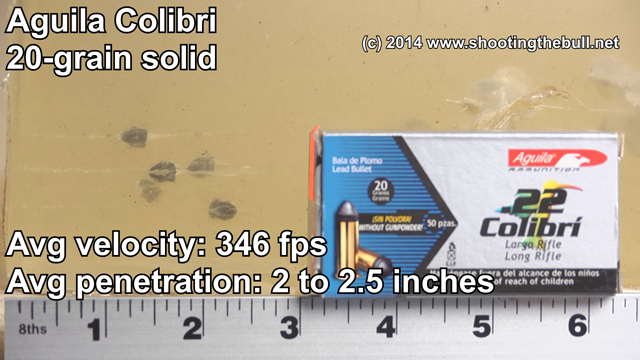

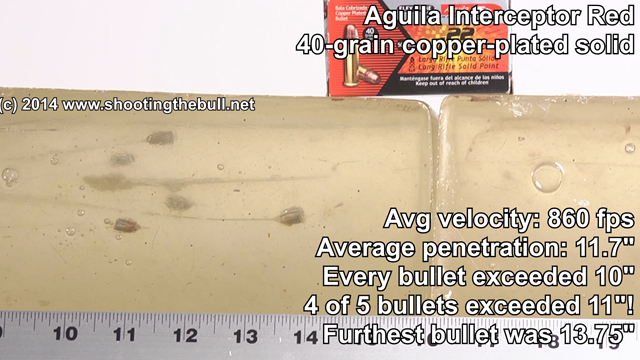

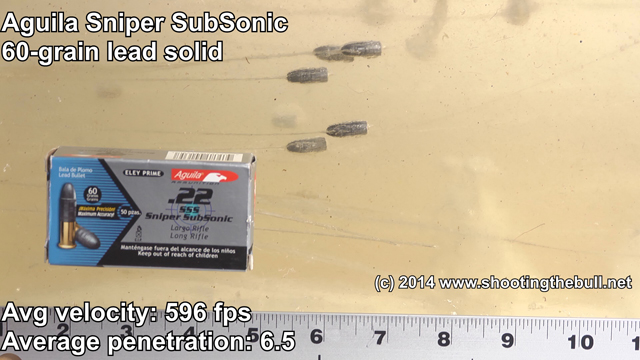

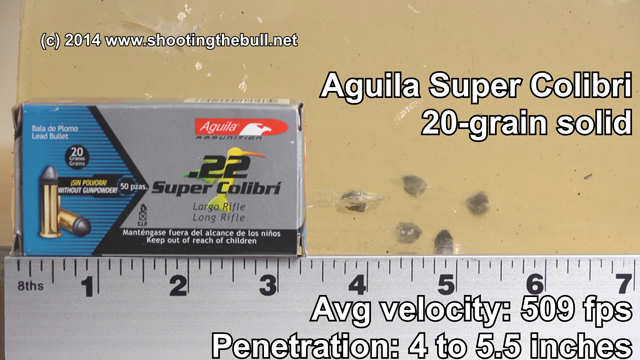

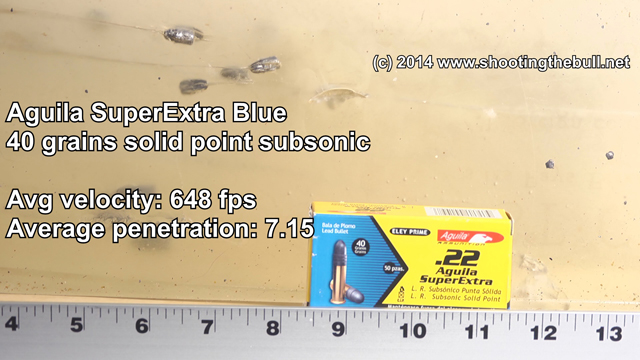

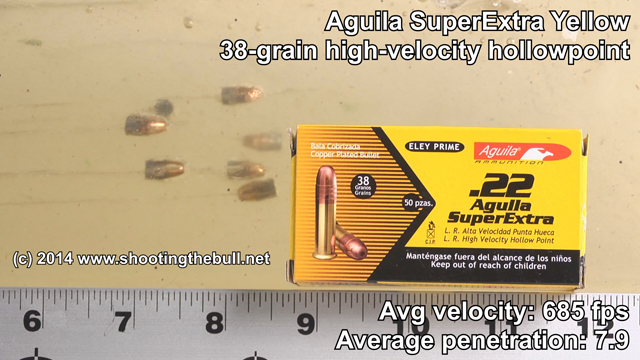

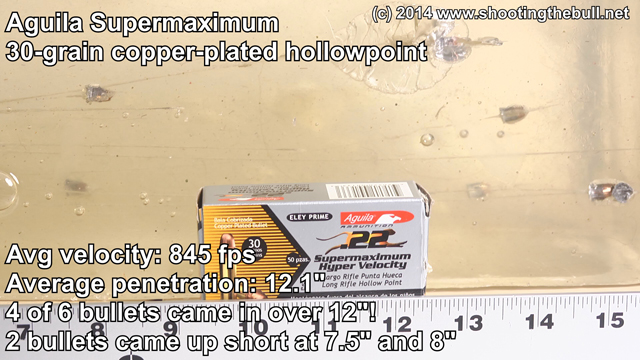

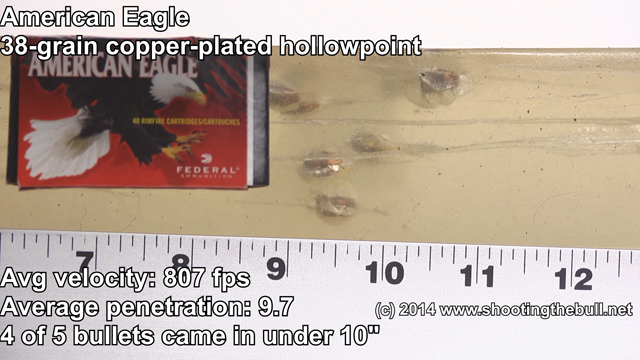

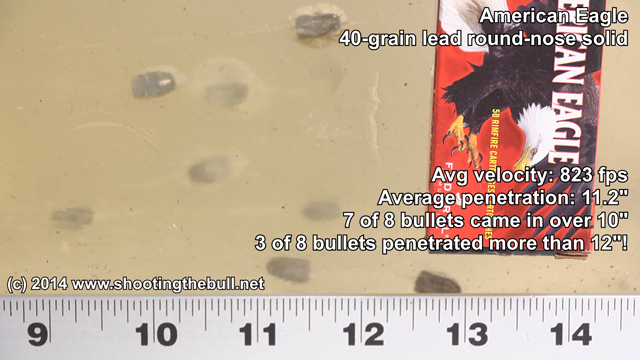

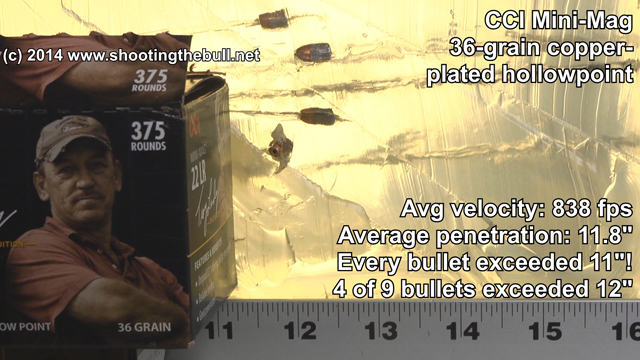

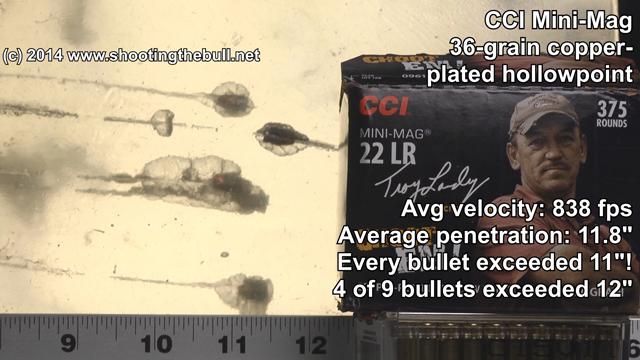

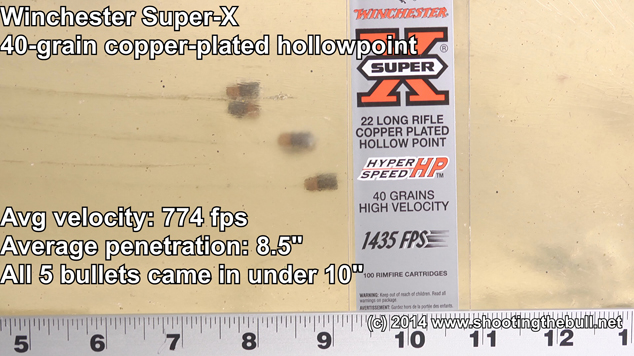

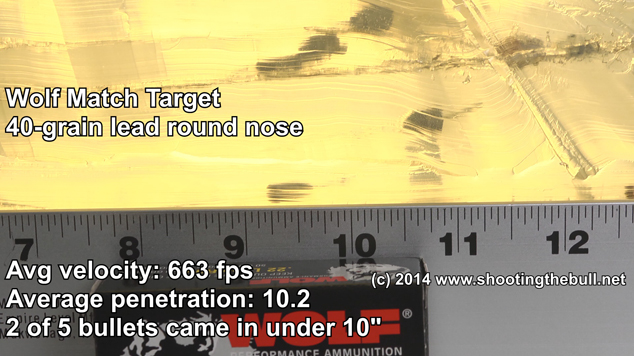

C. Proper ammo tests can show you what type of damage you can expect a particular gun/ammo combination to deliver. What performs excellently from a 6″ barrel might perform pathetically from a 2″ barrel. You have to see the specific combination tested together before you know for sure what type of damage the gun & ammo combination can deliver.

D. In general terms, there actually really is a big difference between the amount of damage the small calibers (.22LR, .25 ACP, .32 ACP, and .380 ACP) can do, and how much damage the “service” calibers (9mm, .40 S&W, .357 Magnum/Sig, and .45 ACP) deliver. A pocket 9mm is a much more powerful weapon than a pocket .380 ACP, for example.

Summary

You cannot assign a “stopping power” value to any particular cartridge, or any particular caliber, or any particular bullet weight, or any particular kinetic energy value, or any particular bullet velocity. These things all have to work together to produce damage in tissue. The more likely that the bullet & gun combo can reach the vitals and the more vital tissue that bullet damages, the more likely the attacker is to stop sooner. You want 12-18″ of penetration capability through ballistic gel and, once sufficient penetration is achieved, you want as big of a bullet size as you can possibly get. A big bullet penetrating deeply and impacting the vitals at high speed will cause damage, and that will stop the most determined attacker. (of course, if you miss the vitals, all bets are off; a hit with a .22 beats a miss with a .44 Magnum any day of the week).

As a final word, I’d like to quote from Evan Marshall. Marshall is the author of several studies on “street shootings” and “stopping power” and his work is often quoted by those who want to talk about “one shot stops”, and his work served as some inspiration for Ellifritz to do the study that’s been under discussion here. So does police officer Evan Marshall rely on specific cartridges or specific calibers for “one shot stops”? Of course not. Here’s Marshall’s advice, quoted from a post made on his forum at Stopping-Power.net:

1st, let me be perfectly frank. I see no benefit from carrying a .380 when I have a 9MM that is sitting inside a front pants pocket inside a Blackhawk pocket holster as this is being typed.

2nd, we need to focus on the right aiming point. I’ve named it the “Golden Triangle”-nipples to nose.

…

Finally, shoot to lock back, drop the pistol, and shoot them with the 2nd gun repeatedly. I only reload after I’m convinced the Super Bowl is over.

If you are not carrying at least two guns you haven’t been paying attention.

My interpretation? Forget the whole notion of “stopping power” by caliber or by cartridge. Don’t try to draw conclusions from data that doesn’t ask the right questions. Instead, choose a gun & ammo combination that delivers as much damage as you can accurately control, and just put your shots on target, and shoot until the threat stops.