WHAT ABOUT BONES?!?!?!

(sorry for shouting, but — I get that question a lot.)

If there’s one common, frequent question I get asked more than any other, it’s — what about bones? Why don’t you factor bones into your equations? Why don’t you put pork ribs in your gelatin tests? Why doesn’t ANYONE test with bones?

I tried to address that subject in a prior blog post (here). But seeing as the question just came up again, I decided to do a little more research on the subject to see if I could present the information in a different way, that may help make it a bit more understandable and approachable.

You Can’t Just Go Shoot Pork Ribs

First thing to face though, is: living tissue and dead tissue are not the same. The dried-out bone that you give your dog to chew on, well, that bone seems like it’s as hard as a brick or made of stone. The living bones in your body, however, are very different — when they’re alive, they’re hydrated, and they’re (comparatively) flexible. Bones aren’t some big impenetrable wall of indestructibility, they’re — living tissue. Harder than other tissue, yes, but still, living tissue. They grow, they get longer, they break, they heal, they’re alive, and they’re very different from the dead hard cow skulls you encounter when wandering through a desert oasis…

… so, back to the question of bones. Why don’t we use bones in gel? Because they’re absolutely unpredictable, they’re not consistent, they vary in size and composition quite a bit depending on the individual, their size, their weight, their level of osteoporosis, and they can vary significantly in their composition (such as whether it’s a thigh bone or a skull bone!) And the penetration or deflection or bullet deformation that happens is absolutely and entirely dependent on the angle that the bullet hits the bone at, and at the angle that bone itself presents to the bullet (i.e., hitting the triangular peak of an arm bone or the rounded edge of a rib is going to affect the bullet very differently from smashing head-on (literally) into the front of the skull. Trying to account for the effects bone would have on a bullet’s performance is a nearly impossible task, due to the sheer overwhelming number of variables involved.

But Let’s Give It a Shot (hah!) Anyway…

However, attempting to solve Herculean tasks can be a little fun, so … I’ll try. A bit. With the understanding that nothing I say here will rule out the freak incidents where a bullet bounces off a skull or deflects off a rib or whatever. We can’t predict those, we can’t rule those out, but we can say those aren’t typical or normal.

So — how much effect does human bone have, on slowing down or affecting a gunshot? Not a whole lot.

(uh-oh, I’ve done it now…)

Okay, stick with me. I know there’s a thousand anecdotes out there, and I know that there are people who know people who know someone who once got shot and their pinky stopped the .44 magnum bullet cold and we’ve all heard about the guy who got shot in the face by a .45 ACP that traveled under his scalp and ended up exiting out the back of his head without ever even penetrating his skull and all that, but — again — those are not the norm! They’re atypical. We can’t account for every possible variation or every imaginable circumstance. All we can do is look at it generally, and examine tissue penetration based on observable science and the laws of physics and in light of the studies that have been done.

In general, we know that bullets go through bones. There are innumerable headshots and chest shots that attest to this. Sure, there are exceptions, but there are exceptions to just about every general observation — it would be foolish to ignore the mountain of evidence and focus solely on the exceptions, right? If we did a study of a thousand suicides through headshots and (say, pulling a number out of a hat) 996 showed bone penetration, and four showed that the bullet bounced off, I think it’s only practical to determine that bullets as a rule do penetrate bone 99.6% of the time, right? Those few cases where it bounced off would be relatively statistically meaningless in the general discussion of whether bullets can and/or do penetrate bones. Note: I don’t KNOW those statistics, so if anyone wants to point a link to a verified study that shows the percentage of headshots that result in the bullet penetrating the skull, vs. the percentage of headshots where the bullet bounced off the skull, I’d be very interested to review that data and update this article to reflect it.

So let’s get to the central question: how much effort does it take for a bullet to go through a bone?

Is Human Bone A Bullet-Stopper?

Not really. In a study in 1968 by Donald F. Huelke, J. H. Harger, and others, they undertook to find out what happens when steel sphere projectiles impact human femurs. Which may be morbid, but it’s also interesting to see, in that very few tests have been conducted specifically and scientifically on human bones. And the femur is the largest bone in the body (although I really would have preferred that they do their study on ribs or the skull, beggars can’t be choosers, and for purposes of our article here we gotta start somewhere so we’ll go with the femur study.)

They fired two projectile sizes, .25″ and .406″ (roughly about the size of a #4 buckshot ball or a .25 ACP bullet, and a .40-cal S&W or a 0000 buckshot ball) at dozens and dozens of actual human femurs, and recorded the damage done to the femurs, as well as the impact speed and the exit speed of the projectiles. In other words, they catalogued exactly what the impact with the bone cost the bullet. Knowing that, we can hope to add to their findings by calculating just how much power the bullet would retain and how much more damage it can do, after having impacted the bone.

(Side note, it’s interesting to me that they determined that embalmed bone was a good substitute for actual living bone. I have not verified that through other studies or sources, but will have to go on their word for now. We know dried-out dead bone is a lousy substitute for living bone, but apparently the embalming process allowed the bone to retain similar properties to when it was living… at least, according to this study…)

So what did Huelke and Harger etc. find?

A .40-caliber ball at as slow as 252 feet per second was able to punch entirely through the bone, although it was only traveling at 40 feet per second after exiting the bone (and, thus wouldn’t have penetrated much further). Considering that the average 9mm round is usually traveling 4x as fast and weighs a good 30% more than the sphere they tested, it’s a pretty safe bet that the 9mm is going to have no trouble going through bone.

So Now Let’s Bust Out The Calculator…

If we examine their data at typical handgun velocities for the size of the rounds, and run the data through the Schwartz Quantitative Ammunition Selection formula, we can determine penetration depths and remaining penetration capability and, effectively, figure out just how much penetration their spheres “lose” from having to first penetrate a bone.

As an example, let’s take a .406″ sphere such as they used. They used a steel sphere, which would weigh a little over 69 grains. A lead sphere would weigh more but, interestingly enough, in a follow-up study they determined that weight was irrelevant for the purposes of determining the damage done; they instead found that size and velocity were the determining factor, so … in interests of keeping this approachable, I’ll substitute in a 90-grain .380 ACP bullet and a .40-cal 000 buckshot ball for the .406″ sphere. They’re not a direct comparison, but they’re relatively similar to the tested steel sphere, at least ballpark similar. A 90-grain .380 ACP FMJ should travel at about 820 feet per second when fired from a 2.8″ micro-pistol, and a load of NobelSport 40-caliber buckshot is rated on the box for 820 fps velocity, so — the parallels are too convenient to ignore, so let’s use an 820fps velocity for the start of our comparison. Using Huelke et al’s data from page 100 of their study, it shows numerous entry and exit velocities for the .406″ sphere. Let’s examine the closest line, which is 814 feet per second, which gives us the most reasonably comparable approximation of our 90-grain round-nose .380 ACP FMJ and our .40-cal buck ball.

According to Huelke et al’s data, the sphere at 814 feet per second blasted through the bone with an exit velocity of 619 feet per second. Using the Schwartz formula, I find that a 69.4-grain steel sphere at 814 feet per second would penetrate 13.04″ of soft tissue, but here’s the fun part — it would be slowed down to 619 feet per second after traveling only 2.44″ of flesh! So what did the bone impact cost the bullet, in terms of penetrating power? Only 2.44″. After passing through the bone, that steel sphere would still be able to penetrate 10.60″.

Put another, simpler way: the steel sphere started out at 814 feet per second, but after passing through a bone, it was down to 619 feet per second. If we fired that steel sphere into muscle tissue instead of bone, it would slow down to 619 feet per second after only 2.44″ of tissue.

So the impact with the bone lopped off about 2,44″ of the bullet’s ability to penetrate flesh.

That ain’t that much.

Okay, let’s try now with the .380 ACP equivalent — 90 grain, .36″ in diameter, so about 10% smaller diameter than the steel sphere. This isn’t going to be exact because, of course, the bullet size isn’t exactly the same, but I warned you at the beginning that we can’t be exact because of the millions of variables present in such an experiment, so … let’s roll with this as another variable, okay? A .380 ACP 90-grain FMJ, which is close to the same weight and close to the same velocity as Huelke’s .406″ steel sphere, when traveling 814 fps will (according to QAS) penetrate 16.48″. In order to bring the velocity down to Huelke’s observed 619 feet per second, how much flesh would the bullet have to cross? Just 3.01″. That’s it. After smashing through the bone and dropping to 619 fps, the bullet would retain enough power to penetrate an additional 13.47″.

Seems like that bone isn’t an impenetrable wall after all, doesn’t it?

Now let’s try it with a more-similar projectile; we’ll use a spherical buckshot ball that measures .40″. This should be exactly the same size and speed as what Huelke et all used, and although the weight is a little heavier for a lead sphere vs. a steel sphere (about 95 grains vs about 69.4 grains), remember that in their follow-up study they found that weight wasn’t a determining factor in the amount of damage done to the bone so, again… we’re gonna roll with it. From a Raging Judge, I measured .40-caliber buckshot as penetrating an average of about 17.56″ (IIRC) into calibrated 10% organic ordnance gelatin. According to QAS, those 96-grain lead .40-caliber buck balls, at 814 feet per second, should penetrate 17.49″. Seems like an ideal comparison point to me… especially because the ammo is rated on the box for 820 fps, so it seems like everything’s lining up. So how much would the bone slow those buckshot balls down? Again, using the exit velocity of 619 fps, QAS tells us that it would only take 3.25″ of flesh to equal the velocity drop that Huelke observed. Now, sure, that’s a drop, but — is it that much? With a round that would normally penetrate 17.49″, shaving off 3.25″ due to bone still leaves it able to penetrate 14.24″ of flesh, after it’s burst through the bone. And that’s still plenty enough to reach the vital organs and disrupt them.

What About A Different-Size Bullet?

In their study, Huelke et al didn’t compare solely .406″ spheres, they also conducted tests from .25″ spheres. We can run a comparison to see how they did simply and easily enough. Let’s take as an example a .25 ACP FMJ bullet, the same diameter (but obviously not the same weight) as their lead spheres. We’re looking mainly for a reasonable velocity here, so — according to SAAMI, a 35-grain .25 ACP bullet should travel at about 900 fps. So for our calculations, we’ll use Huelke’s 900fps data. According to them, at 904 fps, a .25″ steel sphere (which weighs 16.4) grains will blow through a femur and still be traveling 558 feet per second when it exits. Well, using the Schwartz formula, it says a 16.4-grain steel sphere at 904 fps would normally travel 9.67″ through tissue, but it would drop to 558 fps after only 2.75″. Again, this is quite consistent with what we’ve seen from the .406″ sphere, is that having to go through a bone only costs about 2.5-3″ of flesh penetration from a bullet’s total.

Now let’s take a 35-grain .25 ACP FMJ and put it at the same velocity. Unhindered it would pass through 14.91″ of tissue, but if it hit first hit a bone and its velocity dropped to 558 fps after clearing that bone, its total penetration would be 4.24″ less. This is the worst case we’ve seen for how a bone would impact the penetration, and even then — it’s not all that much. From 14.91″ down to 10.67″ is a drop, certainly, but not the impenetrable brick wall that bone may appear to be.

Accounting For The Weight Discrepancy — or, AHAH! The Flaw In The Science!

I said at the beginning that it would be impossible to account for all the variables, but there’s one here that I do want to account for, and that’s the weight difference between steel and lead. In the Huelke study they used steel spheres, not lead balls, and in bullets we typically don’t use steel, we use lead. Trying to translate the impact of steel balls into the impact of lead balls will raise some mathematical questions, but I want to address it because it’s possible someone might think that my conclusions are erroneous because I tried to equate the exit velocity of the lead ball to the exit velocity of the steel ball.

It’s true that Huelke et al did a follow-up study to assert that diameter and velocity of the projectile were the determining factors in bone damage, and that mass was irrelevant. I find such a conclusion challenging to accept on face value, because I know for a fact that mass is highly determinant in penetration. As an example, a steel sphere of .406″ fired at 1000 fps will penetrate 14.95″, but a lead sphere of .406″ would weigh more and, when fired at that same velocity, would penetrate over 20.46″. So I have a skeptical eye towards that part of the study, but I think it’s pretty easily resolvable.

To determine the effect of mass, they fired steel spheres, and identical-sized spheres of Heavimet, which is a tungsten carbide alloy that’s 2.18x heavier than steel. That way they had identical diameter and identical velocity but more mass. Their observed bone destruction was the same between both (which is why I was okay with the idea of using lead bullets as compared to their steel spheres) but — here’s the kicker — they didn’t measure overall penetration! Once it got through the bone, that’s all they were concerned with; they weren’t measuring the ongoing penetration (which is what I, and I think most terminal ballistics aficionados, would be interested in knowing). And, frustratingly, while they measured exit velocity with the steel spheres, they didn’t report exit velocity with the Heavimet spheres. Instead, they only reported the amount of kinetic energy lost, and, further, they didn’t report it as a percentage of impact energy, they only reported it as an absolute number of ft/lbs. Grrr. So, I have to back-figure velocity and energy impact data to figure out what the exit velocity actually was.

Based on the Heavimet study, they say that an 1100 fps steel sphere lost 25.1 ft/lbs of energy by impacting the bone, and a Heavimet sphere lost 26.2 ft/lbs of energy impacting the bone. Because those numbers are similar, they used that as an argument to say that the sphere imparted about the same amount of energy to the bone and cause a comparable amount of damage (which they verified by visual examination of the damage.) BUT — what they’re not saying is that the exit velocity of the Heavimet sphere would be the same! Because it wouldn’t. The additional mass of the Heavimet means it has more kinetic energy, and that mass will help it retain its momentum better. Using their numbers, a Heavimet sphere of 2.18x the weight of steel, at the same velocity (1100fps) would contain 2.18x as much kinetic energy in the first place (96 ft/lbs, as opposed to 44 ft/lbs for the steel sphere). So even though they lost the same AMOUNT of energy, proportionally the Heavimet sphere lost much less of its total energy — and, therefore, we can deduce that it retained higher velocity.

So — let’s go back to our original 814fps sphere and compare for exit velocities. In the original experiment, the steel sphere went 814 fps and weighed 16.4 grains, for a total of 24.12 ft/lbs of energy. And, they say it had an exit velocity of 558 fps, which would give it 11.33 ft/lbs of residual kinetic energy, for a total loss of 12.79 ft/lbs of energy. But a Heavimet sphere weighs 35.76 grains, and at 814 fps it would possess 52.60 ft/lbs. If it lost 17.2 ft/lbs of energy by passing through the bone (which is what their chart shows in table 1 for a Heavimet sphere at 800 fps), that would give it a residual kinetic energy of 35.4 ft/lbs. Well, in order for a 35.76-grain sphere to have 35.4 ft/lbs of energy, it would have to be traveling at about 670 feet per second — much faster than the 558 fps that the steel sphere retained!

So what does this mean?

It means that the numbers I gave you above (2″ – 4″ of penetration lost due to bone) are probably grossly conservative, and the true penetration loss is even less. For example, let’s calculate the 35-grain .25 ACP at 814 fps. Previously, using the steel sphere’s exit velocity, we came up with a loss of 4.24″ of total penetration due to the bone. But that was based on a steel sphere’s mass. Since the HeaviMet bullet weighs basically the same as our .25 ACP bullet’s real mass (35 grains), we can perhaps extrapolate that the velocity loss of one .25″-diameter 35-grain projectile (the Heavimet sphere) will be quite comparable to the velocity loss you’d see with another .25″-diameter 35-grain projectile (the .25 ACP lead FMJ). So, assuming that the exit velocity will be similar, let’ see how much penetration it takes to drop the velocity of the .25 ACP down to the Heavimet sphere’s exit velocity of 670 fps… according to QAS, an 814-fps 35-grain .25 ACP FMJ will drop to 670 fps after traveling through just 1.5″ of tissue.

One More Caveat

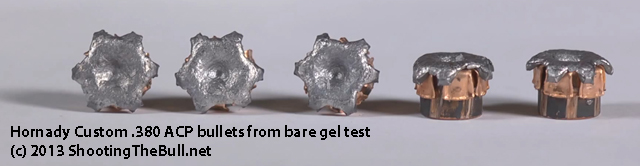

Okay, last monkey wrench to throw in is: this is for round-fronted objects (buckshot balls, steel spheres, or full-metal-jacket round-nose bullets). This doesn’t take into account hollowpoints or bullet deformation that may happen due to impact with a bone.

(Like I said before, there are a MILLION different variables, and it’s going to be nigh unto impossible to account for them all!)

Conclusions? Are There Any We Can Reasonably Reach?

In general, based on our spitballing and on the scientific studies of Huelke et al, we can leap (however unjustified and tenuously) to the conclusion that hitting a bone will usually result in losing about 2″ to maybe 3″ of total penetration. Which pretty much lines up with a study I read a while ago from (can’t remember, was it Fackler, or MacPherson, or Roberts?) where the author tested and determined that impacting a bone caused a drop of somewhere around 2″ of a bullet’s potential penetration. Can’t find that study, I’ve googled and tried to wrack my brains to remember where it was, so if any of my good readers out there know of it and can point me to it, I’d be glad to update this article with a link to it).

Edited 1/28: Finally found a link to what I’ve heard referred to as “The Canadian Study.” This was a 1994 study done by the Canadian Police Research Centre, wherein they tested 9mm and .40 S&W ammo as a potential replacement for their .38 Special duty revolvers. In this test, the CPRC fired about 18 different types of ammo from 9mm, .40, and .38 Special into calibrated ballistic gel — with bones in it! And without, too, but the key point here is — they used bare gelatin, and they also used gelatin with pork ribs embedded in it. They used standardized testing procedures, and they tested in controlled environments, and they used the same ammo and the same guns, with the only real difference being the presence of pork ribs. Now, I said before, using pork ribs isn’t really a good idea since they’re not living, they’re not hydrated like living tissue would be, but — heck, it’s another data point, so why not look at their results and see what they got? The report is 90 pages long, but I’ll boil down the essence of it for you:

.38 Special hollowpoints penetrated 21.8% DEEPER after passing through bone, than they did in bare gel.

9mm hollowpoints from a 4″ barrel, penetrated average of 10% DEEPER after passing through bone, than they did in bare gel.

9mm FMJs from a 4″ barrel penetrated 20% LESS after passing through bone (23.075″) than they did through bare gel (29.1″)

.40 S&W hollowpoints from a 4″ barrel penetrated an average of 4% LESS after passing through bone, than they did in bare gel.

.40 S&W FMJs from a 4″ barrel penetrated 3% DEEPER (29.45″) after passing through bone, than they did in bare gel (28.575″)

So, what can we draw from this study? Bone doesn’t make a whole heck of a lot of difference. Sometimes it actually makes bullets penetrate deeper (attributable to the bone impairing the bullet’s expansion; in the 9mm rounds the bullets in bare gel expanded to an average of .614″, the bullets that hit bone expanded to .593″). And sometimes, the bone slows the bullet down a little (the .40 S&W’s penetrated about 4% less). But in both cases, it amounts to a whole lot of not much, wouldn’t you agree? It’s certainly not the impenetrable Great Wall Of Bone that seems to be a common misconception. And while we can’t take this Canadian study as gospel (because, again, living human bone is not the same as dead pork ribs), it at least gives us another data point, and all the data points we can find all seem to be pointing to the same conclusion: bones don’t affect bullets all that much.

So that’s my conclusion. Hitting a bone does rob the bullet of some potential penetrating energy, but not nearly so much as people seem to think. And if you’re using bullets that have been tested and proven to exceed the minimum 12″ penetration depth, it should still have more than adequate penetrating capability to reach the vital organs and shut down your attacker. And, now you can see and better understand why the minimum required penetration depth is 12″ as recommended by the Wound Ballistic Conferences of 1987 and 1993 — because, frankly, to get to the vital organs of any attacker, it’s almost certain that your bullet is going to have to go through bone (ribcage or skull) to get there.

Now, I know that people would rather see this demonstrated, than read a 4,000-word discussion of it, and I agree — I think it would be an interesting test to run and I’d gladly do it, but — how do you come up with several dozen embalmed human ribcages to test on? I’ll supply the bullets and the ballistic gel, if someone wants to set me up with a couple dozen embalmed human cadaver ribcages!