Interesting thing about “conventional wisdom” or “things everybody knows” — they’re frequently wrong. You know, simple examples like “the earth is flat” or “the sun revolves around the earth”… these are plainly obvious things to anyone with eyes, right? Look around you, and you’ll see that the earth is flat — except for the tiny complication that, in fact, it isn’t. And the prevailing notion that the sun revolved around the earth was not only widely accepted “fact”, it was literally heresy against the Church to say otherwise… even though, in actuality, it was wrong.

It doesn’t really matter how widespread a belief is, does it, if it turns out to be wrong?

Sometimes I think people hide behind false beliefs because “there’s strength in numbers”. If lots of people believe the same thing, then nobody could blame YOU if you believed it too, right? You know, the old “everybody’s doing it” argument?

But — wouldn’t you rather be “right” than “popular”? Hmmm, even as I type that I can acknowledge that there’s probably a lot of people who would disagree… oh well, to each their own, I guess… I know I’d certainly rather believe what is true, regardless of how many other people agree.

Where am I headed with this? Just that I’m challenging one of the most dearly cherished beliefs among shooters: Muzzle Energy, Muzzle Velocity, and specifically the idea that More Kinetic Energy Is Better.

Shriek! Sacrilege!

Of COURSE more is better! How could anyone suggest otherwise? Heretic!

Yeah, I know… heretic. Kind of like that whole sun-revolves-around-the-earth thing, right? Here’s the thing — to me, it doesn’t matter what we WANT to believe, all that matters to me is what is TRUE. I’ll gladly change my beliefs to line up with the truth, any time. Never been one to go along with the crowd anyway.

So let’s talk about “Muzzle Energy”. This is one of the most common ways, and most obvious ways, that shooters judge the effectiveness of ammo. The more “energy” a round has, the better, right? Who could argue with that? I mean, the common conception is that the faster the round, the better. Seriously, if you had a choice between two rounds that use the identical same bullet, and one is rated at 1000 feet per second, and the other is rated at 900 feet per second, and they’re the same price, wouldn’t you have to be a raging idiot to buy the 900fps version?

What if I told you the 900fps version actually penetrates deeper and performs better than the 1000fps version?

For some of you, that feeling you’re experiencing right now is called “cognitive dissonance” — where your brain hurts, trying to reconcile two conflicting “truths” — you know (or at least want to believe) that I’m right, or else why would you be reading this article? But simultaneously, you also know that “more = better” because … hey, come on, it’s faster, therefore it MUST be better, we all know that…

Testing Trumps Theory, Every Time

So here’s where testing comes into play, and where I can demonstrate what I’m talking about and how it’s different. Let’s take the example of Speer Gold Dots in .380 ACP. I got pretty solid results with these out of the 2.84″ barrel Taurus TCP, averaging about 920 feet per second and 11.71″ of penetration through ClearBallistics gel. From a Bersa Thunder 3.5″ barrel, I got substantially higher velocities, averaging 980 feet per second. That’s great, right? That’s “better”, right?

So here’s the head-smacking part — why did I get an average of only 9.5″ of penetration from the 980 fps Bersa Thunder, whereas the exact same bullets delivered 23% more penetration from the shorter-barrel, slower TCP?

It’s Not What You’ve Got, It’s How You Use It

Unquestionably, the Bersa Thunder’s longer barrel resulted in more energy in the bullet than the TCP’s shorter barrel did. By my calculations, the TCP delivered 169 foot/lbs of muzzle energy, whereas the Bersa delivered 192 ft/lbs! That’s a pretty huge difference, yet the relative effectiveness of the bullets were exactly the opposite — the TCP bullets penetrated deeply enough to cause an incapacitating hit, nearly meeting the FBI’s specification for a minimum of 12″ of penetration, whereas the exact same bullet from the Bersa came up way short, not even reaching 10″.

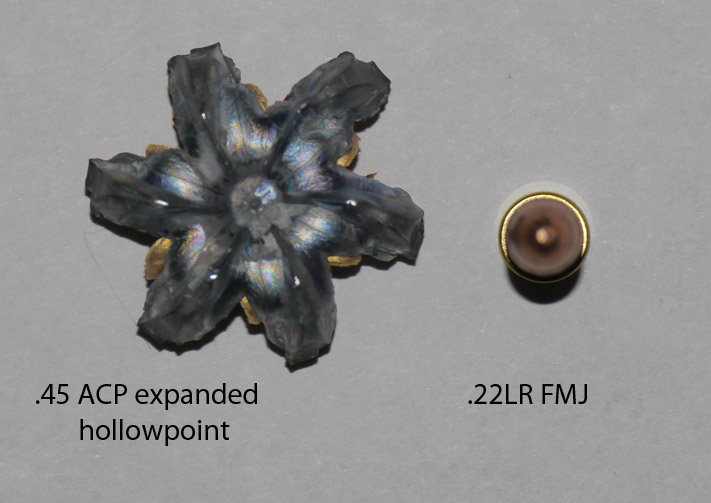

Why? Because the bullets from the Bersa, travelling at such a higher rate of speed, impacted the ballistic gel much faster and spent all that additional energy on EXPANSION, not on PENETRATION. The bullets from the Bersa did indeed have a lot more energy, and they spent it on forcing the bullet to open up to a bigger diameter. The bullets from the Bersa expanded to an average diameter of .515″, whereas the slower bullets from the TCP expanded to only .447″. That’s a difference in overall diameter of about 15%, which doesn’t sound like a lot, but it made a much bigger difference in the penetration (about 23%). The smaller bullet was able to slip deeper into the ballistic gel than the bigger bullet could, even though the bigger-expanded bullet had a lot more energy to it. And, all other things being equal, the bullet that penetrates more is more likely to reach the vital structures of the body and cause an incapacitating hit, than the shallower bullet.

If More Isn’t Better, Then Why Is More Better?

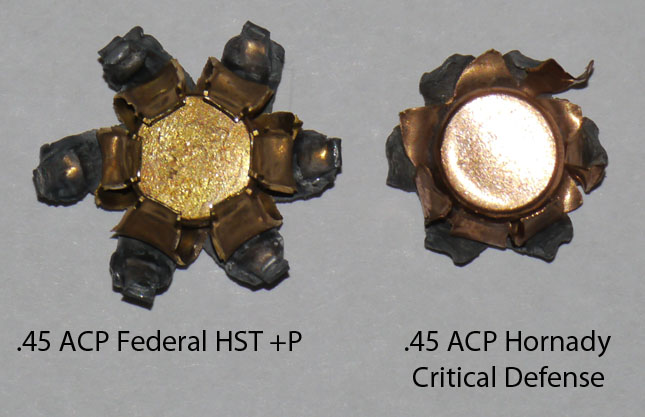

So here’s where we bring it full circle. The natural inclination is to want more, and it seems obvious that we should want more, but — it all depends in how you use it. You CAN do more, with more. Having more energy at your disposal gives you more options than you’d have with less energy. But if it’s not used wisely, it won’t help, and that’s the key. As a bullet designer, spending too much of your available energy on expansion can result in an excessively shallow-penetrating bullet (as I discovered in my tests of the Winchester PDX1, for example). Spending too much of your energy on penetration can result in wasted energy (as in the case of full-metal jacket bullets, which usually penetrate way too deeply and frequently will overpenetrate and exit the body, thus wasting their energy). The ideal situation is where the designer crafts a bullet that expends enough of its energy on getting adequate penetration (ideally 15″, a minimum of 12″, and a maximum of 18″) and then uses any leftover energy for expansion. That would be the ideal tradeoff resulting in the most effective bullet design for self defense purposes. And if there’s so much energy at your disposal that even after you’ve achieved adequate penetration and nice expansion that you still have energy to spare, you can make good use of that additional energy by making the bullet heavier; the more energy you have, the heavier the bullet you can push. And in that context, having more energy can be a great thing — take the example of 9mm vs. .380 ACP. It’s a great illustration because the bullets are in fact identical diameters; the .380 ACP is also known as the “9mm Kurtz” or “9mm Short” or, sometimes, by the 9x17mm nomenclature, whereas the 9mm is also known as the “9mm Luger” and as a 9x19mm. Same diameter, sometimes even the same bullet, but the 9mm Luger cartridge is capable of much higher power. Whereas the .380 is a marginal cartridge in terms of power, the 9mm is much more powerful, and while the .380 requires very careful and meticulous controlling of expansion to achieve the desired penetration, the 9mm has so much energy that it can easily achieve both great expansion and great penetration, even with heavier bullets (the typical .380 hollowpoint is usually about 90 grains, whereas with the 9mm they are usually at least 115 grains and can be as heavy as 147 grains).

So more can be better, when it’s used appropriately. Or more can ruin the balance and give you results opposite of what you intended! Don’t get caught up in thinking that “more always = better”, especially when it’s applied to a term like Muzzle Energy. More can actually get in the way of better performance, as demonstrated by my .380 Gold Dot tests, or my tests of HPR XTP, where the HPR rounds are specifically loaded to less muzzle energy than the Hornady Custom, and actually perform better than the Hornady Custom, even though Hornady Custom uses the exact same XTP bullet, just with more muzzle energy.

Okay, So How Do I Choose The Best For MY Gun?

So how do you know when the ammo makers get the balance right? That’s not an easy question to answer, but the first thing to do is: IGNORE THEIR MARKETING. Ignore claims for muzzle energy and “energy transfer” and “energy dump” and “hydrostatic shock” and “stopping power”. Marketing is marketing, it’s designed to appeal to emotions, which is exactly the opposite of what you should be basing your decisions on. Only valid testing can reveal what will work best — and, only testing that is conducted from a barrel similar to that in your gun, will provide answers that are valid for you! As given in the example above, Gold Dots from a TCP might be quite effective, and the exact same Gold Dots from a Bersa Thunder might be much less effective!

The ideal solution would be for you to test your ammo from your gun. Knowing that not everyone will, or even can, conduct such testing, the next best thing is to look for tests and reviews that were competently done, by people who know what they’re doing, and that were conducted from guns with similar barrel lengths to yours. For the .380, I’ve conducted extensive testing from a TCP, which has a 2.84″ barrel, and as such my results should be directly applicable to those with similar barrel lengths, such as the Ruger LCP (2.75″ barrel) or Beretta Pico (2.7″ barrel) or Sig 238 (2.7″ barrel), etc. But my results would likely not be directly applicable for a Bersa Thunder (3.5″ barrel) or Walther PPK (3.35″ barrel). Those barrels are long enough that they make a significant difference in velocity and muzzle energy, and those differences will mean that the bullet may very well behave differently in how it allocates that energy (in terms of the balance between penetration and expansion).

There is probably an ideal-performing round for your gun, whatever the barrel length. But you can’t rely on “muzzle energy” or “muzzle velocity” comparisons to find that round. Only proper testing will reveal what the best round is — and it may very well be the round with the least muzzle energy, or the slowest velocity. As an informed member of the self defense community, we have to be okay with that. It’s not about bragging rights, it’s about effective performance. After all, I’m okay with my bullet moving slower, so long as it renders the attacker incapacitated.