Probabilities, Not Possibilities

I have a review coming soon on the North American Arms .22LR mini-revolver. And I’ve just done some ammo tests on the North American Arms .22 Magnum Black Widow mini-revolver. And that’s got me thinking about bullet effectiveness, caliber, and some of the misconceptions in the gun world, especially with some oft-repeated statements such as:

“The .22LR has killed more people than any other cartridge in history.”

“The .22LR will kill you deader than crap.”

“The caliber wars are over. Caliber doesn’t matter.”

And that leads us to the holy grail of gun statements:

“The only three things that matter are shot placement, shot placement, and shot placement.”

As with so many other subjects in life, there’s truth in all of the above statements, and all of the above statements can be misused to seriously mislead someone. So let’s look at them and see if we can’t make some sense out of all this — especially in how it applies to armed self defense.

First — the notion that the .22LR has killed more people than any other caliber. Is this true? I don’t know — I haven’t seen any studies done that actually attempt to correlate and compare these figures. It is likely true that .22LR is the most popular caliber in the world, and it is probably true that more accidents happen with .22LR than with any other. It may be true that more youth get involved in accidents with .22LR than other calibers. But even if it ends up being true that the .22LR has killed more people than any other caliber, does that make .22LR the best caliber for self defense? MOST DEFINITELY NOT. For a number of reasons, but let’s start with the first and most basic — self defense isn’t about “killing” an attacker. Armed self defense is about STOPPING an attack. Whether the attacker dies is not our primary focus, and certainly shouldn’t be — after all, if your desire is to “kill” someone, then you’re not acting in self defense, you’re trying to murder someone. If your intent is to immediately halt someone from doing you imminent serious bodily injury or death, that’s self defense — and stopping someone doesn’t have to leave them dead.

Let’s turn to the second statement — “The .22LR will kill you deader than crap.” Is this true? Yes, a .22LR is a lethal caliber that absolutely can kill. A .22LR is more than enough bullet that, if it hits a vital structure, can bring about incapacitation or death. But, again, does that make it an appropriate choice for a self-defense caliber? I would say it has zero bearing on the discussion. Example: when people die from gunshots, is that always because they were shot in self defense? Obviously not. Accidents, and assassinations, are not cases of self defense. .22LR has been used by assassins, with the specific intent to kill — and kill it can — but that cannot be attributed to self defense. So if someone dies from an assassination or from a gun-related accident, what bearing does that have on the legitimacy of a caliber for being appropriate for self defense? None. After all, what use is it to you, if you shoot your attacker in the gut with a .22LR, and they then proceed to murder you, and then drive to their friend’s house, get patched up, but get infected and die three days later from peritonitis? Yes, the .22LR would have killed them — but it would have been useless in stopping them from attacking you.

You should absolutely respect the .22LR. It is not a toy, it is a deadly cartridge — even from as tiny a firearm as a 1″-barrel micro-revolver. It definitely is a deadly cartridge, but it is no more deadly than any other cartridge, and, in many ways, it is less deadly. There is absolutely no terminal effect that a .22LR possesses, that a .380 doesn’t also have*. The .380 does everything the .22LR does, and it does it with much more energy, more mass, and larger size. And the 9mm does everything the .380 does, with even more energy, mass, and potentially larger expanded size. And the .40 does everything the 9mm does, with even more energy, mass, and larger size. Any of them (and, of course, the .45 and all other larger-than-.22 calibers) can kill just as easily as the .22LR can, but the key thing is that any of them are MORE LIKELY to kill (or injure or stop) a person, as the .22LR is.

*(see comment by Aaron below for an example of a unique terminal property of 22lr)

It’s not that the .22LR can’t stop someone, it’s a question of: is it MORE LIKELY or LESS LIKELY to stop someone, than a larger caliber is? And the inescapable conclusion is: it’s LESS LIKELY than the bigger calibers are.

It’s not that it can’t do the job. It’s just that, owing to its tiny size and lower power levels, it is less likely to get the job done than the other, bigger calibers are. It really is that simple.

Of course, there’s a counter-argument here, which says that the .22LR is a more shootable caliber, easier to make more accurate shots with and easier to get back on target due to its lesser recoil. There is some truth to this too, of course, but we’ll explore why this may or may not be a valid counter-argument in the section below on “shot placement”.

Caliber Wars

Next statement on the list: “The caliber wars are over. Caliber doesn’t matter.” As a participant in a few online firearms forums, I’ve seen this type of statement come up over and over. And, usually, it’s repeated by a moderator on the forum. The forums I visit have largely “outlawed” what they call “caliber wars”, and say that the caliber wars “are over”, and all the calibers are equal. Which is patently absurd on the face of it.

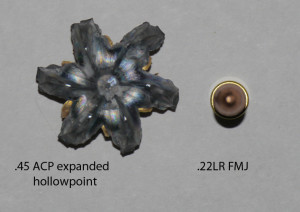

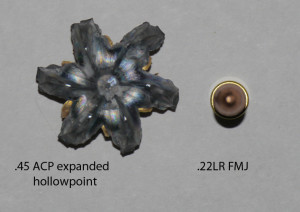

I understand why they do it; I’ve seen caliber wars devolve into what amounts to nothing more than a “pissing match”, and it seems that people are so emotionally invested in their personal choice that they feel they have to defend it at all costs. But it all seems so silly, when the answer is plainly and obviously staring us in the face. Here, let me re-use a picture from one of my earlier articles, about Bullet Size:

One of those is going to do more damage than the other. Both are easily capable of reaching deep enough into a body to hit the vital organs, but one of those is more LIKELY to hit something vital, than the other one is. One of those is more likely to cut a major artery, or destroy the heart, or nick the spinal column, than the other one is. It’s obvious.

For those who insist caliber doesn’t matter, let me turn the question around — say we’re in a scenario where, for whatever reason, you ARE going to be shot. Maybe you’re a mob informant and the mob’s caught you, and their punishment to you is that they’re going to shoot you with one bullet. You get to choose which gun they shoot you with. The choices are either a .45 ACP, or a .22LR. You’re GOING to get shot, so you have to pick one. Which will it be?

I think that answer’s pretty obvious. Caliber DOES matter. It definitely doesn’t matter as much as many other factors, but it does matter.

Which leads us, finally, to:

“The only three things that matter are shot placement, shot placement, and shot placement.”

Okay, hold on to your hats, and keep your keys off the keyboard until I’m done typing, and maybe we can get through this with a minimum of outrage. Is shot placement important? Highly important, yes. Is it the only thing that matters? No. Is it, in fact, the most important factor? Yes. And no.

Here’s where it gets complicated, and hopefully we can try to navigate these waters so it all makes sense. The first and foremost thing is — what the bullet HITS is what’s most important. That’s not the same thing as shot placement, although it is frequently mistaken for such. But let me explain:

When facing a firearm being used for self defense, human beings will stop attacking someone for a variety of reasons, but they can be boiled down into two categories: voluntary, and involuntary. And in many of these cases, caliber doesn’t matter, but it might. And shot placement doesn’t matter for many of them, but it might.

Voluntary reasons

There are many reasons an attacker may choose to stop attacking you. Sometimes merely seeing a gun might be enough for them to say “hey, wait a minute, hold on, we’re cool, I’m just gonna walk away.” That may happen, but even then, caliber may matter. For example, someone getting a face-first view of a six-inch barrel .45 revolver might be MORE LIKELY to be dissuaded, than that same person might be if they instead got a face-first view of a .380 pocket pistol. Once again, it’s not a question of “will this be effective” or “will this be ineffective”, it’s a question of “which is MORE LIKELY to be effective”? I think it’s a fair assessment to say that someone MIGHT be more likely to back off when they see you carrying a Dirty Harry-style big revolver, than they would be if they saw you had a North American Arms .22LR mini revolver. So in this case we have an example of someone who could be dissuaded by seeing a gun, but even then, the caliber might make a difference. Now, can we find cases where someone backed off after being faced with a .22LR mini-revolver? Certainly. But just because it CAN happen, doesn’t tell us how LIKELY it is to happen. And it doesn’t invalidate the argument that it is MORE likely that someone will be dissuaded by a bigger gun, than they would be by a littler gun.

But let’s move up the ladder — let’s say they see you have a gun but they don’t stop. Some of those attackers MIGHT be persuaded to stop, if the gun was pointed AT THEM. There’s a difference between them seeing that you have a gun (maybe holstered, or even held in a low-ready position) and seeing the muzzle of the gun pointed at them. Sometimes merely the change in perspective of seeing down that barrel is enough to get an attacker’s bravado to dissipate and to get him browning his shorts. And this could be a case of where an attack was stopped, without a shot ever having been fired. Now, is it possible that someone might call off their attack if they saw a pocket .380 or a tiny .22 magnum pointed at them? Yes, of course it’s possible. But is it LIKELY? I don’t have the stats to answer that question, I can only pose the obvious follow-up: is it MORE likely that they would stop, if they saw a bigger pistol pointed at them? Again, I think it’s obvious that there are some people who will not be stopped by just seeing any size pistol pointed at them, and there are some who will definitely not be stopped by just seeing a pistol (any pistol) pointed at them. But there’s a group in the middle, those who wouldn’t stop at a micro-pistol but WOULD stop when facing a behemoth. And that’s the group at the heart of this question — is it more likely that someone would stop, if they saw a bigger pistol pointed at them? I believe it is more likely. I think it’s obvious that there is some percentage of encounters that would be stopped by virtue of the defender having a bigger pistol, than would be stopped in the identical same circumstances if the defender had a smaller pistol. Again, it’s not a question of whether a small pistol CAN stop an attacker, it’s a question of how LIKELY it is that the small pistol would be able to stop the attack.

Group Three: Seeing & Hearing A Gun Go Off

Okay, let’s move on. Let’s assume that we’re facing an attacker who will not stop just because he sees a pistol pointed at him (regardless of the pistol). That means we’re going to have to fire the pistol. Now, obviously, you should never draw your pistol unless you’re prepared to fire it and you are in such a dire circumstance that you believe firing it to be necessary to save your life (or innocent life, or to otherwise meet the local and state statutes that govern the permissibility of using deadly force). Maybe you’ll get lucky and before you fire, the attacker drops his gun or knife and backs off, and you won’t have to even discharge the weapon — but maybe you won’t, and you have to fire. Is it possible that merely firing the gun might get someone to stop? Most definitely. Even if you miss, sometimes the muzzle flash and the deafening bang are going to trigger a response in the attacker that gets them to back off. In a case like this, does caliber matter? Again, we don’t have statistics to refer to, but I’d think it matters less than in the other cases. If you get to this point, it’s pretty obvious that the attacker isn’t impressed by the size (or lack thereof) of your gun, but I would have to think the sensory stimulation and attendant adrenaline rush that’s going to happen when they see that blast and hear that explosion, are going to affect them whether it comes from a bigger or smaller gun. If there’s a possibility of dissuading them, the physiological reaction to a gunshot may make them rethink their actions, and it may not matter whether it comes from a bigger or smaller gun. Put another way, I don’t think they’re going to calculate in their heads what the size of the sound was, I think the fight-or-flight instinct will kick in regardless of the magnitude of the blast — and, let’s remember, sometimes little bullets can put out an incredible amount of noise and flash. A .22 Magnum or a 5.7×28 can be incredibly loud and have a huge fireball associated with them. So, I don’t know whether caliber would make someone MORE likely to stop from experiencing the flash and sound, but I doubt it. I think this one might be a case of caliber not mattering.

What About Getting Shot?

Now we move on to the next level — what if they are NOT dissuaded by experiencing the flash and noise of a gunblast? Well, they move up the ladder of reasons why a gun might stop someone: next stop, getting hit. For some attackers, the experience of getting shot might be enough to stop them from wanting to continue attacking. Now, remember, we’re still talking about an attacker CHOOSING to stop. Getting hit by a bullet, any bullet, is likely to be a really unpleasant experience, a feeling of intense pain followed by seeing blood bursting forth. That can frequently be enough to get an attacker to call off the attack. And, if that’s the case, does caliber really matter in that situation? Again, I think probably not. I don’t think people who get shot are really cognitively assessing their situation and thinking “I got shot, but it’s only a .22, so I’ll keep attacking.” I think it’s more along the lines of “ack! Pain! Blood! Stop!” Remember, we’re talking about an immediate incident, not some protracted long event — there’s a rule of thumb that says most defensive gunfights follow the 3-3-3 rule: they take place at 3 yards or less, with three shots fired, and are over in three seconds. That’s not a lot of time for thinking and evaluating; that’s more of the realm of instinct and thoughts of self-preservation. In my opinion (again, unbacked by studies to prove one way or another), I think the sensory overload of gunshot/blast/sound/pain/blood combines to make an immediate decision — the attacker will either immediately stop, or will not be affected. I don’t think the caliber is likely to be involved in this decision-making process. As such, I doubt caliber is that important for this level of attacker.

Involuntary Incapacitation

At this point, we’ve pretty much exhausted the opportunities for a voluntary stop. If the attacker has faced this ascending ladder of prospects and has chosen to continue to attack, then there’s pretty much nothing else that is going to make them choose to stop. Heck, they’ve had a gun pointed at them, they’ve been shot, they’re bleeding, and they’re still coming at you. What else can you do?

At this point, you have to rely on your gun’s ability to physically incapacitate them. What do I mean by “incapacitate”? I mean, take away their capacity to attack. Actually physically render them unable to attack any further. And for a handgun, that’s not easy — it means you are going to have to damage the vital structures of their body in such a way that they physically cannot continue their actions.

To force an immediate stop, typically that means you need to damage their central nervous system (specifically the brain stem, or the spinal column). The brain stem is an on/off switch for a human being — if it is damaged, the person ceases to exist. Immediately. If you damage their spinal column, they will no longer be able to control their actions (i.e., they will be paralyzed, or worse). Those actions will immediately stop an attack, instantly. The brain is a less-likely immediate incapacitator; many people have been shot in the head and survived. They may lose some functionality, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they will lose ALL functionality. The brain stem and spinal column are guaranteed fight-stoppers. They are also extremely hard to hit, being very small.

The other way to bring a fight to a very quick stop is to do substantial damage to the circulatory system. Destroying or substantially damaging the heart, major arteries, or other substantial circulatory system damage can cause the attacker’s blood pressure to drop below the level necessary to sustain consciousness. An attacker who passes out from blood loss will be unable to continue their attack. Again, they don’t have to die from the injury in order to stop, they just have to lose consciousness. It is not easy to imagine a scenario where someone has substantial enough damage to their circulatory system that they pass out, but still manage to survive, of course, but we’re not trying to kill, we’re trying to stop, and damage to the circulatory system or central nervous system are the only known ways to reliably and predictably bring a fight to an immediate (or extremely quick) close. Damaging the circulatory system may not result in immediate incapacitation; even complete destruction of the heart could leave someone with enough oxygen in their system and in their brain to be able to act for up to 10 to 15 seconds, so circulatory system damage is still not immediate, but it will result (within about 15 seconds) in involuntary incapacitation. They won’t have a choice — once their blood pressure drops low enough, their body will force them to stop.

So the question is: does caliber matter, in bringing about involuntary incapacitation? Yes and no. A confusing answer, but let me try to simplify it — it’s not about whether a caliber CAN bring about involuntary incapacitation, because frankly they all can. Again, it’s about how LIKELY it is, for any particular caliber to be able to bring about involuntary incapacitation. A .22LR to the brain stem will result in the immediate death of the attacker just as quickly as a .45 ACP to the brain stem will. A .22LR to the spinal column will result in the same immediate paralysis as a .45 to the spinal column will. In both cases, hitting that central nervous system will result in immediate incapacitation.

The question is: how LIKELY is it to hit the spinal column with a .22LR, vs. how LIKELY is it to hit that same spinal column with the .45 ACP (or 9mm or .40 or other larger-than-22 caliber?) It is my contention that the much-larger bullet maintains a higher likelihood of hitting the target (and things near it) than the tiny bullet does. Put another way, the tiny bullet leaves no margin for error. The larger bullet gives you more options; an inch-wide bullet means that you could miss the spinal column by .78″, and still hit it with as much damage as the .22 bullet. If the large bullet is aimed left of the spinal column, but a quarter of an inch of its outer edge still manages to hit, then it will do as much damage as the .22 would if the .22 shot were placed squarely right on the spinal column.

Here we can see — it’s not a case of whether the .22 CAN incapacitate, because clearly it can, but by using the larger bullet you put the odds in your favor that you will be more LIKELY to incapacitate the target.

Same thing applies to the circulatory system. You might place a .22 shot right next to the heart, right next to the superior vena cava, where the bullet slips right between these vital structures, hitting nothing, and doing only a minor flesh wound. Whereas with the .45, with the identical same shot placement, there’s so much more bullet there that it might rip the superior vena cava and the heart both, causing rapid blood loss and forcing incapacitation.

With a bullet hitting where the yellow arrow points above, and identical shot placement, a small caliber might result in effectively a non-event, whereas a large caliber might be an effective fightstopper.

That’s not to say a little bullet can’t be a fightstopper… it can. It’s possible. It’s just less likely, is all. You’d need extraordinarily precise shot placement with a .22 to bring a fight to an immediate stop. If you used that exact same precise shot placement with a larger caliber, it would bring the fight to the exact same stop. But the larger the bullet, the less precise your shot placement needs to be, to get equivalent fight-stopping performance. The bigger the bullet, the MORE LIKELY to end the fight. Even if it’s a small increase in probability, the more likely you are to be able to end a fight, the better off you are. Which brings us to:

“The only three things that matter are shot placement, shot placement, and shot placement.”

Sigh. This is one of those statements that gets trotted out with the intention of immediately ending all discussion. I can imagine that many times, people who bring this statement to the discussion somehow think that they’re telling us something we don’t already know. Seriously, who doesn’t know this? We all know this, yet the dispute remains.

So while we’re already disputing, let me rock the boat significantly by saying “Shot Placement Ain’t Everything.”

(and yes, I’m ducking behind the furniture, knowing that the tomatoes are going to start flying).

But — look, shot placement is important, but it is not the end-all and be-all. It’s close, but wrong, to assert that shot placement is the most important factor. It’s not where you place the shot that is important, it’s WHAT THE BULLET HITS. Now, lots of people will think that’s the same thing, but it isn’t.

If the bullet hits the spinal column, it will bring the fight to an immediate halt. So, surely, advocates of the “shot placement is king” theory would advocate aiming for the spinal column, right? No? Why not? Ah, yes, because the spinal column is a very tiny target and extremely difficult to hit. Right. Got it. But if the bullet DOES hit the spinal column, the target is going down, regardless of what caliber hits it.

Similarly, the brain stem — it’s nearly impossible to hit, and I’ve never heard anyone advocate that you should aim for it, since the brain stem is located at the top of the highly-flexible and highly-mobile neck. But if you were able to hit it, the attacker would stop.

If you’re still with me, here’s where the whole discussion takes a turn — what if you don’t hit where you aim at? What good is “shot placement” as a theory, if the bullet takes a turn? And bullets do, occasionally, take a turn. Some will be deflected off bones, some will just plain turn in a different direction. When bullets hit flesh, it’s not a guarantee that the bullet will stay on the path that you sent it on. Especially with small-caliber bullets like .22LR, their light weight and weak momentum leaves them especially susceptible to turning and veering off course. So even if you put the bullet perfectly on target to hit the brain stem, there are chances that it may deflect or turn off course and only end up hitting flesh or fat.

The above is an example of a .22LR bullet fired from a mini-revolver. Actually there are several shots in that block, and you can see the various damage tracks that show what directions the bullet went. A few went basically straight, but you can see where one took a turn upwards and exited the top of the block, and you can see the highlighted track where the bullet entered straight but then just turned downwards and ended up a good three inches off target. Sometimes, bullets just don’t go where you told them to.

And that’s why “shot placement” isn’t nearly as important as “what’s hit.” If you placed your aim squarely at someone’s heart, and the shot veered off and hit the spinal column, that person will drop immediately. If you placed your aim squarely at someone’s spinal column, and the bullet veers off and hits only a lung, then that’s not likely to take them out of the fight right away. Sure, it might slow them down, but it’s a case of where your “perfect shot placement” wouldn’t have actually done all that much good.

So what you HIT, is much more important than what you AIM AT. Now, obviously, it’d be nice if those were the same thing, but unfortunately they aren’t always the same. We can’t predict what the bullet WILL or WON’T do. But there are factors at our disposal that can influence HOW LIKELY the bullet is to do what we want. How can we put the odds more in your favor that you hit what you aim at? Well, practice helps, obviously; you have to be able to hit where you’re aiming. But that doesn’t solve the problem of the bullet veering off course, or deflecting off a bone. So what does?

Mass. Momentum. Size. Caliber. Once again, these factors come into play. A small lightweight 30-grain .22LR may be highly susceptible to changing direction in the flesh, but it’s unlikely that a 180-grain .40 S&W or a 230-grain .45 ACP will be so easily deflected. Again, it’s POSSIBLE that the heavier bullet might turn or change direction, but it is not LIKELY that the heavier bullet will turn as easily as the lighter bullet will.

I’ve shot thousands of rounds of various calibers into ballistic gel (without bones) and can tell you, definitively, the heavier bullets are MORE LIKELY to stay on course and go where you told them to go, than the lighter bullets are. I see more course changes and veering bullets from .22, .380, and 9mm, than I do from .40 and .45. And I see more course changes in 115-grain 9mm, than I do in 147-grain 9mm. As a general rule, the more mass and momentum the bullet has, the more likely it is to keep traveling in a straight line. That’s not an absolute rule, but it is an accurate predictor of the likelihood that a bullet will go straight.

And the more likely the bullet is to keep traveling in a straight line (and avoid veering off course), the more likely it is to hit what you aimed at.

Which makes your shot placement more effective.

Boiling It All Down

So what does this all mean? To me, it means that there are some things you can do to put the odds more in your favor. While it’s POSSIBLE to stop a fight with a micro-pistol or mini-revolver, those are less likely to stop a fight than a bigger pistol would be. It’s possible that a .22LR pistol might bring a fight to an end, but identical shot placement from a .45 is more likely to bring that fight to an end.

There are things you can control, and there are things you can’t. You can improve your accuracy through training. And you can improve your ammo performance through testing and selection of better-performing ammo that works best with your chosen pistol. If you have the choice of carrying the NAA mini-revolver, or the Glock 19, you would be better armed and stand a better chance of ending any potential fight with the Glock 19. That’s not to diss the mini-revolver, I have one and I love it, but I wouldn’t want to rely on it as my primary defensive weapon, because a bigger caliber pistol (such as a Springfield XD-S) puts better odds in my favor that if I had to use it, it might bring any potential fight to a quicker end, in many ways. It’s easier to aim, it’s easier to control, it places the bullets more accurately, the bullets have more power to them, they have more mass and momentum, and they expand to a much, much larger size.

The first rule of gunfighting is “have a gun”. And as we discussed above, just the presence of a gun, regardless of caliber, might end many potential defensive encounters. So caliber isn’t everything, of course. But as you ascend the ladder of reasons why an attacker might stop, you’ll see that the more power you can bring to bear on your side, the more likely you are to end a fight quicker and more successfully. Sometimes the tiny mini-revolver or pocket pistol is all you can carry — and if that’s the case, then, hey, do so, but with an understanding that these little pistols are less likely to end a fight quickly, than a bigger pistol would be. And whenever you have the choice, go for the more powerful weapon. Put the odds in your favor as best you can.